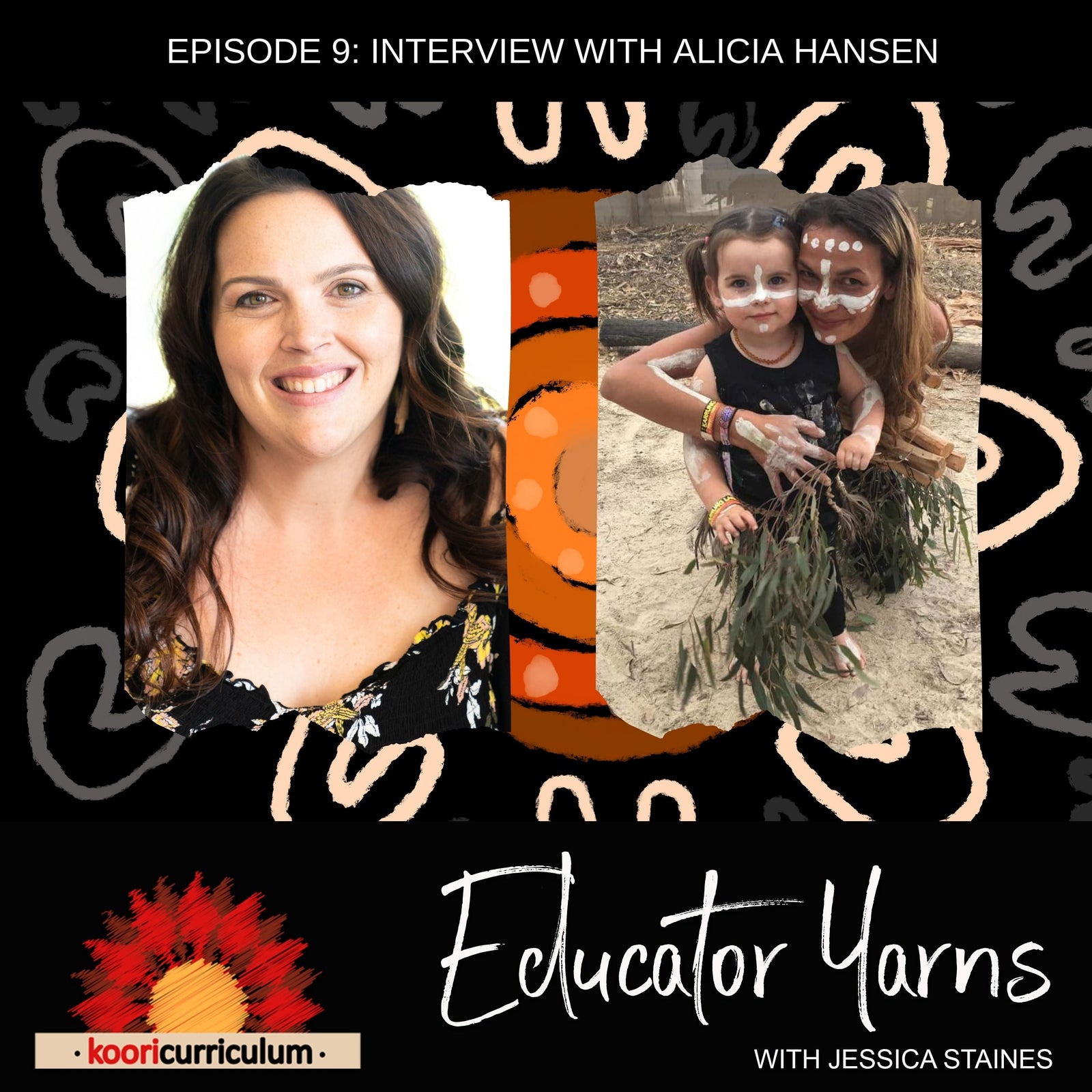

Educator Yarns Season 2 Episode 9: Interview with Alicia Hansen

Today Jess Staines speaks with Alicia Hansen, a Menang Woman of WA country currently residing in Victoria where she works as an Indigenous Preschool advancement strategy facilitator across 83 different centres.

Alicia talks about the importance of creating a welcoming and culturally safe service when facilitating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander enrolments. Jess and Alicia also reflect on their face to face work with educators as they seek to build relationships with their local Aboriginal community.

SHOW NOTES

Today Jess Staines speaks with Alicia Hansen, a Menang Woman of WA country currently residing in Victoria where she works as an Indigenous Preschool advancement strategy facilitator across 83 different centres.

Alicia talks about the importance of creating a welcoming and culturally safe service when facilitating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander enrolments. Jess and Alicia also reflect on their face to face work with educators as they seek to build relationships with their local Aboriginal community.

SHOW NOTES

Alicia:

If we're doing something but is not for the right reason, then it's not going to be effective to anybody. You could have 10 Aboriginal families in there. That's a community within itself. I think it all comes back to that "Why?" We need to find that "Why?" The educator's listened to the child, she's followed the child's needs, the interest, and the learning has occurred. It's about being accepted into your community, and finding that connection, and the connection that's right for you, with the right community.

Speaker 2:

You're listening to the Koori Curriculum Educator Yarns with Jessica Staines.

Jessica Staines:

I'd like to acknowledge the Darkinjung people, the traditional owners of the land on which I am recording this podcast. I pay my respects to their elders, both past, present, and emerging, and pay my respects to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander listeners.

Hi everyone. My name is Jessica Staines, director of the Koori Curriculum. For those of you that aren't familiar with our podcast, season two is all about our new book, Educator Yarns. We're meeting and interviewing with our educator contributors from right around Australia, who will be sharing little snippets of their piece.

It will be a combination of stories about why embedding Aboriginal perspectives is so important, how to connect with local community, how to embed Aboriginal perspectives in our programme, how to work with anti-bias approaches, and so much more. So make sure you listen in and enjoy the episode. Bye for now.

Today's podcast's guest is Alicia Hanson, who has been working in early childhood educational sector in Victoria for almost 20 years. Starting off as an assistant, she quickly found her niche and found herself managing a long daycare centre of 105 children for nearly a decade.

From there, Alicia commenced her studies at night school and found her inner cultural self. Alicia is a proud Aboriginal woman from the descent of the Minang people in Western Australia. Finding this missing link gave her the confidence to move into the role of Aboriginal Best Start Facilitator for the Dandenong community. It was here that Alicia's culture was able to be ignited and grow within her. This gave Alicia the confidence to become an advocator for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and their rights.

Alicia is a firm believer that every child can learn and have the opportunity to be self proud. Alicia is an amazing person, and I'm so excited for you to be able to read her article in Educator Yarns, and listen to her yarn this morning. So, welcome Alicia.

So, thanks so much Alicia for writing for us and for jumping on our podcast today.

Alicia:

You're very welcome. Thanks for the opportunity, Jess.

Jessica Staines:

So, I thought we just might start this morning with you just giving a bit of some context about who you are, and where you work, and what you do, and who your mob is, and all that whatnot. Is that all right?

Alicia:

Sounds great. So, my name is Alicia. I currently live on [inaudible 00:02:59] country. My background is I'm a proud Minang woman from the [inaudible 00:03:05] nation over in NWA. My husband to be is a [inaudible 00:03:10] man. So my daughter is also a [inaudible 00:03:13] and Minang little girl.

Currently at the moment I'm working as the indigenous preschool advancement strategy facilitator, which is a section I oversee in Victoria. And I advise kindergartens with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander enrollments, and I oversee 83 kindergartens.

Jessica Staines:

Well, that's just a small job that you've got. No pressure at all there.

Alicia:

No pressure. No, not at all. So I've got about 170 children enrolled in my programme. So it's just fantastic. And we have the KPIs of getting educators to be culturally aware, and having welcoming environments and making sure that children's attendances are as high as everybody else's, and they have a smooth transition into their next stage of learning, being a primary education.

Jessica Staines:

Mm. And that's one of the things that I often talk to educators about why this work is so important. And for me a big part of that, "Why?" Is to make sure that our kids start school with their best foot forward, and they're not starting school on the back foot.

And when you're looking at that transition to school, that you're not just looking at that from a child's perspective, but from a family's perspective as well, and how you're preparing families for that schooling. You know, because a lot of our families didn't have positive experiences during their formal schooling. Do you find that is something that you encounter in your role?

Alicia:

Absolutely. I try to get educators to look back at that Bronfenbrenner philosophy of the brown onion, and the looking at it a different way of there are those layers that you actually need to unfold and peel back and acknowledge and understand, before you can get to that middle core, which is the child.

So flipping Bronfenbrenner and actually saying, "Well you need to undo all of those layers, and finding out those layers can be grandparents, aunties, older brothers, other children that are already in care that aren't living with the family." Every family is individual, and what their onion actually looks like can be quite tedious, sometimes opening up. But once it is open, to ensure that that inside layer is able to come out and actually flower, I think is highly important.

Jessica Staines:

I love that analogy. That's awesome, and it's a really unique way, and a great way of understanding and looking at Aboriginal kinship and family structure. So that's awesome.

So when you're working with educators, so most of your educators are in mainstream, early learning services and not Aboriginal specific services, is that right?

Alicia:

A hundred percent.

Jessica Staines:

So with those educators, obviously most of them probably being non-indigenous, what do you think is the main support or obstacles that they are facing?

Alicia:

I think the main support I can give them is that face-to-face contact. I think they find once they've actually spoken to me, it's okay. But when I actually go into the service and visit them, their confidence is able to then grow, and be able to go, "Look, you're doing a fantastic job. We're all starting this together, and there's really no right and wrong."

I think it's hard for educators, and it's still just that fear of getting it wrong. And I think when an Aboriginal person can enter the centre and they can actually feel that you feel welcomed, provides the support that they're looking for to be able to move into the next stage of putting it into the curriculums.

Jessica Staines:

Yeah. And I feel that whole thing about getting it wrong, it's just so common. And nearly every guest that we've had on the podcast has talked about this fear that educators have in getting it wrong. And I don't believe in that saying like it's better to just [inaudible 00:06:50] at all, because I think that that lets people off the hook a little bit too easily. I think some things that we do can be detrimental, when there hasn't been consultation, or there hasn't been that understanding of why they're doing it.

And you know, but that's very rare that that happens. And most of the time it's when you're working with educators that have deeply ingrained biases, and so forth. And it's unfortunate when you encounter that. But those people are definitely the minority, I feel, in our profession. I feel that most educators really do want to do the right thing. And often because they have so much anxiety around it, they're even more thorough in their approach, to ensure that they're taking the right processes and taking the right step. [crosstalk 00:07:39].

Alicia:

Yes. Yep. And I also personally feel that there actually hasn't been a time when I've heard of some educator coming to me and saying an Aboriginal person was highly offended by something that I did [crosstalk 00:07:50].

Jessica Staines:

No.

Alicia:

I actually haven't heard of that. And I appreciate the non Aboriginal early educators treading carefully, I suppose. But there has been no research or data to prove that we are going to get our back up or something. So I just ... I believe what you're saying, well, it's just a bit of a ... I don't know, not a very good excuse anymore.

Jessica Staines:

And I feel like sometimes when we go to centres, like obviously we see things that probably aren't best practise that are [crosstalk 00:08:19].

Alicia:

Sure.

Jessica Staines:

But most of the time, like I just sort of feel like here these educators are, who I know that are anxious, but despite that are giving it a go-

Alicia:

Yes.

Jessica Staines:

... and doing [crosstalk 00:08:29] the best of their ability, because they value the importance of doing the work. So if they're there investing their time, and they're willing to learn, and they're willing to listen, well, I'm willing to help.

Alicia:

Yes.

Jessica Staines:

So I really respect educators that step up to the plate and give it a go, you know? And I think part of the thing is, is that there's so much conflicting advice out there, about what's okay and what's not okay. So for example, one of the educators that wrote in our book, talked about how she works really closely with children teaching them about totems, and children have selected their own totems and stuff like that.

Now see that to me, I think, "Oh gosh, that's really ... You're walking a slippery slope, going down that path," right?

Alicia:

Yes.

Jessica Staines:

But see, for her in her context, [inaudible 00:09:17] done that in partnership with her local Aboriginal community, with local elders who had been saying to her, "This is what we want. This is what [crosstalk 00:09:26]. This is what we want you to do."

So I think that's fine. But then in the next community, a couple of suburbs over, they might have a really different philosophy and protocols around do they want that to happen or not happen, and so forth. So I think that's why the main thing that we encourage educators to do, like the number one thing, is to form those relationships with community, to make sure that they're able to stand behind their programme with integrity and respect.

And just like you said, every family is unique. Every family's onion is unique. Every Aboriginal community is unique as well, in terms of what they believe is okay and not okay. So do you see that diversity, even between these 83 services that you're working with, what's okay in one area, versus another?

Alicia:

Absolutely. Because I cover such ... it's a very wide area I cover, it's the old Grampians region. So it's crossing about three or four different countries, and then it's crossing about four or five different government LGAs. So what might be okay in one service, in one town ... So I had a service whose family came in and the little boy wanted to do his totem and put it on a pole, and put it out in the garden. And I quite personally don't see anything wrong with that. The educator's listened to the child, she's followed the child's needs, the interest, and the learning has occurred. Completely, absolutely fine in my eyes.

But then her local council said that that wasn't okay, because she hadn't done what they believed were all the protocols of her connecting to the community. What the council didn't take into consideration is that where she's actually located, the land hasn't actually got specific traditional owners in place yet.

So she's in a little bit of what you would call no man's land. So what is she supposed to do, not do something for this child, or continue on with these child's interests?

So I find it very difficult. Some services have great connection. They had local Aboriginal people living next to them; I don't even need to give them any assistance. Whereas some, I need to go in and actually have that conversation with them, and their managers, to let them know that protocols are different everywhere. What is right?

And you've got to look at the community of the kindergarten as well. So what makes up the community of that area, then when you make up your community kindergarten it's different as well. You could have 10 Aboriginal families in there. That's a community within itself.

Jessica Staines:

Yes, that's right. And you know, sometimes there's conflict within communities about directions that people want to take. And a lot of the time that people, they're made up of traditional owners of that place, and then Aboriginal mob that have moved there from other nations. Like yourself, like you're ... I think you're married to one of the traditional owners, though. You've married-

Alicia:

Yeah, one day we'll get married, yeah. But yeah, he's a traditional owner, and my family's originally from WA. So does that mean we don't incorporate my child's ... on my side for my child's learning, because she's on [inaudible 00:12:36] country, or [inaudible 00:12:37] country?

Jessica Staines:

This is it. So there has to be that balance-

Alicia:

Yes.

Jessica Staines:

... between including local cultural perspectives. And you often privilege that, because that's the country that you're based on, and living on, and so forth.

But we also go broader than that, because I think a lot of people grew up thinking that we were Aboriginal full stop, and not understanding the diversity of first nations peoples that were many countries, were many different mob, and we are very different.

So with that understanding, I think that we have to show the diversity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and reflect that in our classroom curriculum, you know?

Alicia:

Absolutely.

Jessica Staines:

It's a hard task for educators really. Like a) to get the confidence just to start. But then once you begin, you just realise that you're only really scratching the surface, and there's just so much to learn, there's so much to know, there's so much to do. And it really is, I know people are so sick of this word, but it really is a journey.

Alicia:

[inaudible 00:13:42].

Jessica Staines:

It is a journey. So do you find it in your area? I think the role, like having you as a support for these services is amazing. So I think that. And I often say that Victoria is leading the way in terms of support workers, and Aboriginal organisations and leaders that can work with schools and early learning services to do this work. Whereas in new South Wales where I am, it's very ... there's not a lot at all available that's put out there.

But one of the things that I find educators really struggle with is making connections with community. And I know that even yourself, when you first moved to that area, you wrote in your piece about some of the struggles that you had forming connections. Do you want to share a little bit about that?

Alicia:

Yeah. Well, I was just going to say, as you were talking about how it's hard for the educators to understand, it's also hard for us as Aboriginal people to understand too. Like, well, I wasn't raised as an Aboriginal, knowing that I was Aboriginal. It was not until I was about 12 years old that it was confirmed that yes, our family is of Aboriginal descent. And that still didn't come about until I was about 24, 22.

Now I'm the youngest of three, and I'm the only one that's highly connected to community through my ... and my brothers aren't. My brother is an Aboriginal lawyer, but he doesn't have the connection for community that I have with the Dandenong mob. So when I first started there, I just waltzed in, I thought, "Yep, I'm Aboriginal. Let's just get this done. Speak your mind."

But it's not that way. It doesn't really matter if you're Aboriginal, Chinese, Sudanese, or Muslim, or Christian faith. It's about being accepted into your community, and finding that connection, and the connection that's right for you, with the right community.

For me, it was difficult. It was a little bit shameful that I thought I would be able to just be an Aboriginal person and it would just come of naturally. I was walked into the co-op and a beautiful auntie of mine walked out and she said, "You're not Koori girl." My mum said my face just dropped. And she looked me dead in the eyes and she looked me up and down. She goes, "You're a Minang woman." And I was just like, "Wow." And that for me then resonated, that we are all different. We're not the same. You can't just walk into that Koori co-op because you think you're Koori. No, I'm an Aboriginal woman, and I'm from Minang, and I'm a [inaudible 00:16:11] person.

So for me, that was where my connection was then just ... the universe just opened for me. And it was like, "Oh, I can get it now. Like, we're not all the same, we all are different. And we all carry different traits and different stories and different journeys."

So for me, that was a very big eye-opener. And to be able to then be ... open up my doors, I think, and let the community know who I was, and why I was there. Because there's always a why, why we do something. We don't do something for no reason.

And then that's when the acceptance and the connections were all formed. They could see that I was just looking to almost find myself, and my place. I was feeling a little bit lost. And then when it was all found, I became feeling quite whole about myself.

So I think if you look at non Aboriginal people, and then Aboriginal people trying to find that connection, they could draw very much on my situation and my story, and my journey of how I became to be such a strong, proud Aboriginal woman, and be able to advise. Very much like you Jess, when we first started initially in education, people just turned to us and expected us to know the answers, when we don't; we have to go and find those answers and make those connections.

So if we can do it, I think everybody can do it. It's just the time and the, "Why?" Having your, "Why?" Clear, and knowing that you're being true to yourself and the community as to what's happening.

Jessica Staines:

Mm. I think you just need to be honest about who you are, and transparent about it, and the position that you have. Like for me, I'm really upfront. I was brought up outside of community. Whilst we always had relationships and connections community, it's not the same as living and being in an Aboriginal community. I don't know if that makes sense to you, but you know what I mean?

And that is different. Like my worldview is different, you know, being a [inaudible 00:18:04] woman that grew up in Sydney, that now lives on the Central Coast. Like my identity as a [inaudible 00:18:12] person is very different to someone that's [inaudible 00:18:17] that lives in Orange or in Condobolin or, you know what I mean? Like whilst we all have culture, and we all identify what that means for each of us is different, because there's more to our culture than just our heritage. You know, it is our geographical location plays a part in our identity. So does our education and relationships, and individual interests and gender and sexuality. Like all of those things impact on somebody's cultural identity, and expression, and sense of being.

And that's why one of the best things that you've said, and I love it, is that you need to take each family, and each person as you find them. And whilst we need to have some general knowledge and understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities, and our history and so forth, we all are human beings, and people. And so it's important not to generalise, but get to know each family and each child on that individual level. Because what's important for your family is different to the next.

And it is hard sometimes even for me with working with Aboriginal communities. There are some Aboriginal communities that are really welcoming and accepting, and there's others ... Or not communities, I would say like individuals within communities, who are a bit more standoffish and hesitant and-

Alicia:

Oh, absolutely. Yes.

Jessica Staines:

And that can be triggering for people here Alicia that are living off of country, to not feel displaced, and to feel like you have a place, and that sense of connection and sense of belonging, you know?

Alicia:

Yeah. That just because we're not on country, we still need to find that connection, I think.

Jessica Staines:

That's right. It can really challenge our sense of identity I feel, when ... You know, and these are issues that I think a lot of Aboriginal people have, and we can go down that whole rabbit hole of talking about lateral violence and so forth, but ... And there's levels of that, you know, but it's-

Alicia:

I think it all comes back to that, "Why?" We need to find that "Why?"

Jessica Staines:

Yeah.

Alicia:

And why we're something. If we're doing something but it's not for the right reason, then it's not going to be effective to anybody. It's just going to be detrimental to everybody. So I think if you bring it back to that, "Why?" why am I not living on country, and why am I feeling this way? Then we can process a little bit better, I think.

Jessica Staines:

Mm. That's right. And look, I think for me personally, like I ... a really strong, in the sense that we get asked to talk about lots of different topics, and for lots of different service types. Like we get approached by insurance companies, and to talk to them about reconciliation, and all sorts of things. But, you know, I never do that work, because there are other people, there are other mob that are better qualified to do certain things than what I am.

But I feel like my space is to talk about early childhood and curriculums, and how non-indigenous educators can make their programming and planning more inclusive and welcoming of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Like that's what I feel that my space is, and where I have a strong knowledge that ... Whereas I think if you want to talk about language or totems and spirituality and so forth, I feel like there's other people out there. And that's why there's such a strong emphasis on the importance around listening to multiple voices, and different points of view, is that it's not this one stop shop sort of thing, where you can just talk to me, and listen to us having these podcasts, and then it's all done. And it's that spectrum and that continuum journey that educators are going to be embarking upon.

Alicia:

Yes. And I think that's the beauty of my role, is because I've been doing it for, I think nearly four years now, or maybe even five, that the educators and I have been able to form a relationship where it's workable. They know that I don't have all the answers. My husband, my family, and I don't have all the answers, but I can help you find the person who does have the answers.

Jessica Staines:

That's right.

Alicia:

And I think it's been more of a hand-holding process. Like, "I'll hold your hand and take you to this other person. And eventually I'll step away when you're both ready."

Jessica Staines:

Yeah. That's a beautiful way of looking at it. You need to be that bridge sometimes for educators, so that everyone feels supported; that community feels supported to engage in those relationships, as well.

Alicia:

Yeah. And that they know that when they do engage, they're going to be heard and listened to. There's a difference, I feel, between just being heard, and then being listened to as well.

Jessica Staines:

Mm. Yeah. Yeah, very true. I am ... For educators that are listening to the podcast, that aren't one of the lucky ones that are one of your 83 centres, what would you suggest for them, in terms of connecting with community as a place to start? Like if they've got no connections at all, how do they begin?

Alicia:

Hmm, that's a good one. I think it's hard for educators at the moment, because they're just ... they've got so much paperwork and so much ... They don't have enough time away from the children, to get out and make these connections. These connections aren't going to happen through emails.

Jessica Staines:

Yeah.

Alicia:

They're going to happen when you confront ... not confront, but when you show up. You need to be present. You need to find invitations, and make invitations for Aboriginal people to come and visit you.

And when they do come, it's just about forming a relationship. It's not about what they can bring for you, and what you can give them. It's just about being and supporting each other, I think. So finding avenues where you can invite Aboriginal people, just to come in and have a look and see if they feel comfortable to be in that service, and make that relationship. Finding community barbecues, that you might be able to offer something for the children. Use your experience as your forte. Go and turn up to the local playgroups and offer toys and resources that they might not have.

Go and offer to do a story time or make Play-Doh with the children. Don't expect anything back though. Just be clear to say, "I'm here because I'm looking to help. I'm looking for a relationship. This is what I'm after. This is my "Why?" This is who I am." And just be very clear and honest with yourself first, before you go and try to make any connections.

Jessica Staines:

Yeah, I agree. I think that's one of the things that educators say is that, "Oh, well, I emailed this person or I tried to ring them and they didn't get back to me," and so forth. But it doesn't work that way, you know?

Alicia:

Right.

Jessica Staines:

So I think being there in person and making a real life connection is so important with trying to build that rapport and to build that trust. And one of the opportunities that often educators can utilise is during NAIDOC week or reconciliation week, where community is coming together, they're gathering together. So you can attend those events and develop a bit of a stakeholder's list; work out who's who in the local community, to begin making those connections, and then continue them on. I know right now it's really hard, because a lot of events are happening online. So I feel like-

Alicia:

[inaudible 00:26:13] make it easier though, kind of? Like you can-

Jessica Staines:

Sometimes, yeah.

Alicia:

... say you're showing interest in a Facebook event. And I was going to say it is NAIDOC week through Victoria at the moment. And to be aware of NAIDOC week, and it is ... it can be very draining on us as well, because there are so many expectations.

Jessica Staines:

Yeah.

Alicia:

So just going in, like you said, just trying to work out who's who, and who does attend these things. But it's also acknowledging how much drain and pressure is put upon Aboriginal people through certain ceremonies, and certain celebrations. And those types of things also is highly important as well, I think. But use what we've got to our advantages. It's all online at the moment now. So now's the best time to try and get your fingers in the honeypot, I think.

Jessica Staines:

Yeah, for sure. One of my girlfriends says though, that, whilst we appreciate support during NAIDOC week, like we're black the whole year long. So, you know-

Alicia:

Exactly, yeah. Don't just come through NAIDOC week; it's all of the time.

Jessica Staines:

Yeah. That's right, "It's NAIDOC week, so what are we going to do?" Or like, "Who can we get to come and do something?" and all that sort of stuff. It's like, "No, no, we've got ..."

And look, one of the things that we started to do during NAIDOC week is we used to take it off. Like I used to not work at all during NAIDOC week, because I wanted to have ... I did the first couple of years, and then I never got the chance to connect with community either, you know?

Alicia:

Yes. Yep.

Jessica Staines:

[crosstalk 00:27:35] working and doing things for other people. And I was just like, "No look, I need to take the time for me and my family, and reconnect and do what I need to do too. So-"

Alicia:

And you just said there Jess, it's about taking the time and connecting and reconnecting.

Jessica Staines:

Yeah, that's right, you know?

Alicia:

It's all about just taking the time and connecting and reconnecting and reconnecting.

Jessica Staines:

Mm. Yeah. Thanks so much Alicia, for jumping on the call this morning. I really appreciate it. And thanks again for writing in our book.

Alicia:

It's been lovely having a yarn with you.

Jessica Staines:

I know. It feels like we haven't seen each other in ages.

Alicia:

I know.

Jessica Staines:

Normally like [crosstalk 00:28:09] months we see each other doing something. And now it's like, "Ah, I miss my second home down in Victoria," you know? Like-

Alicia:

Yes. It's beautiful down here.

Jessica Staines:

Anyway. So hopefully it's not too long before we catch up again. But cheers again, and we'll talk again soon.

Alicia:

Hopefully I'll have you down in Jan.

Jessica Staines:

Yes.

Alicia:

Yes. Thank you so much, lovely. Have a great day, and I'll speak to you soon.

Jessica Staines:

Right. Bye.

I hope that you enjoyed this episode and had a great little sneak peak between the pages of our new book Educator Yarns. If you'd like to ask questions or connect with me, best to join our Facebook group, the Koori Curriculum Educator Community, which is free for all of our listeners and members.

On our next episode of Educator Yarns, I'll be meeting with Cath Gillespie, an educator at Evans Head preschool. We'll be yarning about nature play and pedagogy, and how she is celebrating Aboriginal culture in her nature classroom.