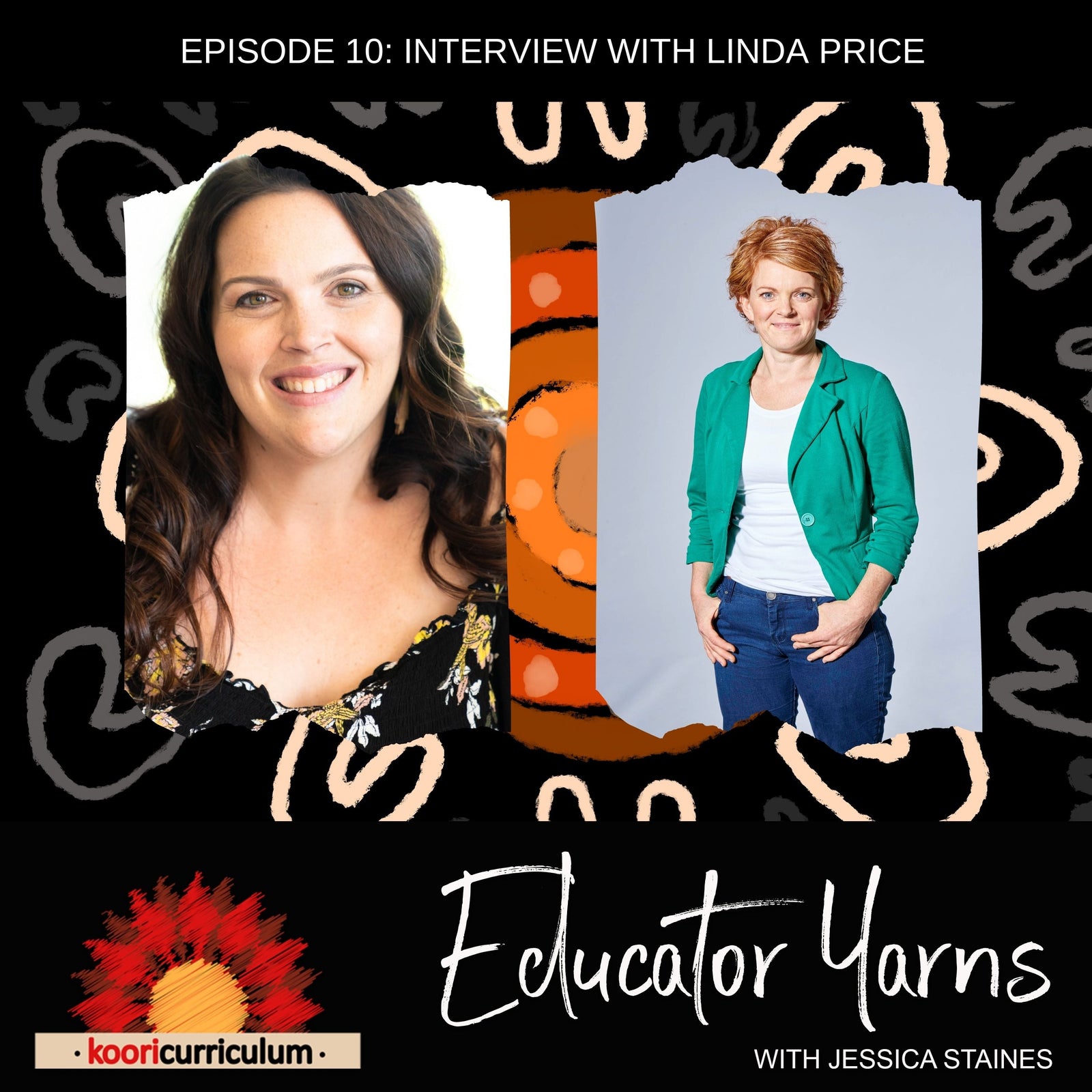

Educator Yarns Season 2 Episode 11: Interview with Linda Price

Today on Educator Yarns Jessica is joined by Linda Price from Kinglake Ranges Children’s Centre on Taungurung land in Victoria

Linda reflects on how drawing upon her own passion and understanding of seasons from her home in New Zealand equipped her to use the local Taungurung seasons to embed a deeper connection to local Aboriginal culture in her curriculum.

SHOW NOTES

Linda Price:

But if we can all create a community of learners and learn together, what that does is that it takes a bit of the pressure away and it allows for room to make errors and to reflect on those errors and to correct yourself, and to move on.

Jessica Staines:

Your children need to have a love of country before they learn respect for it.

Linda Price:

It was really easy to point out the language of country to the children because you can see it and feel it.

Speaker 3:

You're listening to the Koori Curriculum Educator Yarns with Jessica Staines.

Jessica Staines:

I'd like to acknowledge the darker young people, the traditional owners of the land on which I am recording these podcasts. I pay my respects to their elders, both past present and emerging, and pay my respects to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander listeners.

Hi everyone. My name is Jessica Staines, director of the Koori Curriculum. For those of you that aren't familiar with our podcast, season two is all about our new book 'Educator Yarns'. We're meeting and interviewing with our educator contributors from right around Australia, who will be sharing little snippets of their piece. It'll be a combination of stories about why embedding Aboriginal perspectives is so important, how to connect with local community, how to embed Aboriginal perspectives in our programme, how to work with anti-biassed approaches, and so much more. So make sure you listen in and enjoy the episode. Bye for now.

In this episode of Educator Yarns, we will be meeting with Linda Price and early childhood educator working at Kinglake Ranges Children's Centre in rural Victoria. A few years ago, she developed a Bush Kinder programme in response to some of the challenging behaviours she was experiencing among children within the centre. Knowing the benefits of mental health with time in nature, the programme was designed to specifically target mental health as a priority for the children.

What she did not expect was the strong connections to country that they would forge along the way and the added feelings of belonging that it would invoke across the entire community. We're so excited to be 'yarning' with Linda and to have her as a contributor to our 'Educator Yarns' book, where she really does share how she has used her strength of nature, play and pedagogy as a way to embed Aboriginal perspectives in part of her day-to-day programme.

Thanks so much for joining me this morning, Linda, and I thought we'd just start if you're able to just introduce yourself to our listeners and tell us a little bit about your teaching context.

Linda Price:

Sure. So I'm Linda Price. I'm one of the early childhood teachers at Kinglake Ranges Children's Centre, which is a rural centre located about 65 kilometres north of Melbourne. So Kinglake Ranges is probably well known for being the epicentre of the Black Saturday bushfires, and that kind of gets me into the context of our centre, and the setting where I'm from. I teach at a centre where we've got childcare and integrated three and four year old kindergarten programmes. I'm currently the teacher for the three-year-old kindergarten programme and also the Bush Kinder programme. That's kind of where we're at and how we established.

Jessica Staines:

Yeah. Great. And so how often do you take the children out into the Bush Kinder? How does it work?

Linda Price:

Our Bush Kinder runs for three hours a week for each child, so in our four-year-old kindergarten programme, we had fifteen hours of fun to kinder. We have three of those hours in our local parks at Bush Kinder. In reality, we've got four small groups throughout the week. We've got Bush Kinder for all of our four year olds, and this year we've had an opt-in programme for our three-year-olds, as well. This is our first year of rolling it out for three-year-old kinder. On a Wednesday and a Thursday, that's when our Bush Kinder is, so each of those children enrolled in that programme will have three hours either in the morning or the afternoon, and either on a Wednesday or Thursday.

Jessica Staines:

Okay, great. What really struck me about your piece was, how you are putting an acknowledgement of country into practise and really teaching the children about their role as being custodians of the land and I think it's important. We get a lot of emails from educators saying, "Well, how do we start our acknowledgement of country with our children?" And something that you said, and I think you might've quoted David Attenborough in your article, but it was something along the lines of, "Children need to have a love of country before they learn respect for it." Something along those lines?

Linda Price:

Yeah, absolutely. I kind of wanted to help establish an acknowledgement of country with the children for a long time, but I've had to, as you say, get them along on this journey. So we started by helping ... well, we actually started by picking up rubbish, to be honest, that's kind of how we started. We talked about the impact of human activity on the Bush and on the animals, and the children through our modelling. It took a little while, but they started to be able to point out the rubbish. Then they suddenly just took on this love of the area that they were in, because they'd been visiting it over and over and over again. They were starting to see, and really connecting with these little places. They had these little play spaces that they would name their own, that they would give their own words such as the skate park or the water park, or whatever it was.

And it was through establishing that love. It's taken a few years, I think, and I've grown along with that programme as well. Once they've got that love of the area that they're in and starting to starting to see those really strong connections to our Bush Kinder area and therefore the wider community. That's when I could start to say, "Actually, I think they're kind of ready for this now." And I had a group in 2019 last year who just absolutely were taken with acknowledging all the things about Bush Kinder that they loved, and that's where we started. Then we started bringing in the acknowledgement of country.

Jessica Staines:

So I think with acknowledgement of country, it does take time and it is a process. I think it's less about what you get the children to say and recite, it's more about those actions and the relationship that they have with place and their understanding of place. I know that part of that journey for you was working really closely with the Kulin seasonal calendar?

Linda Price:

Yes.

Jessica Staines:

How did that come about? How did you source the information for that?

Linda Price:

Yes, so that did start for us at the Melbourne museum. I was looking at one of the exhibitions, the First Peoples exhibition, and also there was information at the time on their website. For me, I was trying to find a way that I could start to make those connections with country and start to include other aspects of culture within our programme in an area where none of us had really been done before. I wasn't really too sure about how to go about doing this, just like many other educators are. I found that when I looked around and really started to notice the changes within our environment, they really lined up with the Kulin seasons, the information that I found. So when we're at our Bush Kinder site, it was really easy to point this out, point out the language of country to the children because you can see it and smell it and taste it and feel it. You can feel all these changes.

And for us, there's been some really key things that, over the years, have started to drive our procedures, and that's around those Kulin seasons. So when we changed into wattle season, for example, we teach the children that this is when the warmer weather is coming, when silver wattle flowers, and when that happens, the snakes will start to come out. There's some really important messages there for anybody who lives on country, and particularly who lives out in a rural area like we do, ways that you can help to understand what changes are going happen, and that can change the way that you operate in and do things.

Jessica Staines:

Yeah. It's interesting how those plants ... So I'm up on dark and young country on the central coast and when the wattle blooms, you're right, it does start to get warmer, and that's part of our seasonal calendar too. It's also when we start seeing whales migrate.

Linda Price:

Yes.

Jessica Staines:

It's interesting how different ... and I know for Dharawal people who are South of Sydney, that's when they see eels in there in the fresh water. Some plants are used in various seasonal calendars in different areas, and they can signify behaviours of different animals, depending on the region that you're in.

That's why I sort of encourage educators, when they're thinking about creating like a Bush Tucker garden or something like that, to really plant native to their area and not just native to Australia in general. Because even if you can't find that information at your local museum or ... the Bureau of Meteorology is also a really good website to check that seasonal info.

Linda Price:

Okay, good.

Jessica Staines:

But even if I can't find that by just observing the changes of the native plants and then observing different animals and birds and weather patterns and so forth, they can almost start to track and create their own seasonal calendar. Because essentially, that's what Aboriginal people did traditionally. It was noticing, observing, and then responding to country. That's how it works.

Linda Price:

Yeah. And that's exactly what we've been doing, as it turns out, kind of not so formally. One of the things that has struck me when I was at Healesville sanctuary, there's a lot of information there, mostly about the Kulin nations and in particularly about the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nations, but it's all relevant to us.

When Muyan, the silver wattle, flowers early, that can signify a long, hot, dry summer ahead. So for us, in a bushfire zone, that's really critical information. For me personally, I really watch that. I'm actually really looking for it. In effect, it actually changes the way that I manage my own property, and it changes my bushfire management plan for my own self and my family, based on what's happening there. I mean, it's not the only information that that feeds in, but it certainly is. When Muyan's in full flower at the start of July, we're probably going to have some extreme fire danger days that year. Interestingly, that's also the year where the Gang-gang cockatoos come down into our area. So those are two things that we've noticed that can signify that we've got a really long, hot, dry summer coming up. So that can be ...

Jessica Staines:

That's important information for people to know. I think this is it. That's what Bruce Pascoe's book 'Dark Emu' really made a lot of people take stock and notice that traditional owners have the answers to a lot of the climate extremes that we've been seeing, like whether it's flooding or fires and so forth. If we pay attention to traditional Aboriginal land management practises, we can prepare for them, and we can also counteract some of these effects that we're seeing happen.

I mean, the Bush fires that even happened in the beginning of this year affected our family personally: my uncle lost his property down the South coast. And I think with that, like uncle Noah had been saying for a really long time that he had been asking permission to back-burn and so forth, or what we refer to as 'Fire-stick farming', and was denied it by council. As a result, he lost a hundred acres of his Bush property where he lives. I think people are learning the hard way that our custodians have the answers to some of these problems that we're experiencing.

With the children at your service, what are some experiences that you would do with them on a day-to-day that embed Aboriginal perspectives?

Linda Price:

There are some really easy things that we do. I think one of the biggest things I can think of at the moment is in our Bush and everywhere around where we live, there is evidence of the Bush fires. Even though it's 11 years later, you see dead trees everywhere. Just last week with our three-year-olds, we were walking through the national park and we were looking at the concepts that I learned through a book published by Dixon's Creek Primary School made with a Wurundjeri elder - uncle Dave, I believe - called 'Parent Trees Are Talking'. We were talking about the importance of having those really old, really big trees in the forest and how they're important for habitat and how they're important for providing shade for the younger plants to grow through.

We also can point out the Upside-down trees, and these are the dead trees that look like they've being pulled out of the ground and flipped upside down, and it just their roots in the air. The children at our centre, they understand about bushfire, I mean they're only three and four and five, but they understand that this got burnt in the bushfire. They understand about all those kinds of things. So they've got a really good platform to help to push that learning. That's one of the things. And there's also been a lot of logging in our area, so we've been talking about the importance of not doing that and how it's been people have been cutting down old growth forest. So we're kind of bringing a lot of those conversations in. At the same time we've been using the Taungurung Language app and the Taungurung Language kit that the Taungurung clans developed, and that's been instrumental in instigating and embedding language within our programmes as well.

For example, all the children now know that if they don't put their lunch lids on their lunchbox, 'bawang' - magpie - 'bawang' is going to come down and take their lunch. A little while ago, the, the children decided to get together and make a nesting station. We call it 'bawang bunnings'. It was really cool because I'd talked about how the 'bawang' had been coming at my house and taking all the coconut husk out of the hanging baskets. We happened to find some coconut husk in the shed at work, so we got out the hammers and nails, and they've decided they wanted to make some little [peck pink plates 00:16:13], kind of 'bawang' bunnings station. We were nailing on the husks and putting it all around the kinder, the garden, and watching what they were doing.

Their use of languages is fabulous too. With that, comes that awareness of diversity and therefore the acceptance of diversity. In effect, it's not about acceptance, it's actually about celebrating the diversity within our community and the diversity within people.

I'm not sure if that's answered the question necessarily, but there's many things that we try to do on a daily basis. Even simple things like if we're doing a deep dive on language and literacy, let's make sure that we're actually incorporating language from lots of different perspectives, and language and literacy can mean so many different things. If we've got alphabets out, for whatever reason, then we also make sure that we've always also got Aboriginal symbology that's relevant for their understanding alongside all of those things.

Jessica Staines:

That's a classic example, that you're not trying to make it separate from what you're already doing. It's embedding it in and having them both. So it's not the in the exclusion of other cultures, it's about having both perspectives there all the time. That's great.

Linda Price:

Well, we're on a journey, so that's ultimate. We've got a way to go yet, but that's where we're headed.

Jessica Staines:

For educators that are just at the very beginning ... And I think you've given lots of good information about developing your own cultural knowledge through museums and resources that you've sourced locally, that it's been a process, That it's very place-based, what you're doing, like it's contextualised to your community. Obviously the bushfires having been there, that mark that it's left on your community is well ingrained, I think. As you said, children that weren't even born when these bushfires were occurring still know what bushfires are, and can see evidence of that in the community around them.

For educators that are looking at generally wanting to start and develop more knowledge on custodianship and caring for country, what are some resources or places that you would point them in the direction of?

Linda Price:

I suppose the first thing is if I think back a few years, there's a lot of professional development that's available such as through yourself, Jessica, and also even simple things like through ECA Australia, they have reconciliation path one and two modules, that's probably the absolute baseline awareness out of nothing. There's a lot that you can do without it being particularly difficult so that you can actually build up your own confidence in your own knowledge. I think for me, I certainly took on the approach of learning together instead of teaching. Because to be a teacher, it's expected that you're an expert and I'm certainly not, and I wouldn't want to suggest that I ever was. But if we can all create a community of learners and learn together, what that does is it takes a bit of the pressure away and it allows for room to make errors and to reflect on those errors and to correct yourself and to move along the journey.

I did a lot of professional development first, just basic things. Then from there, I suppose I tried to find the one thing that, for me personally, was easy enough to use as a starting point. Because I grew up on a farm and I actually grew up in New Zealand, but my dad was really connected to his land. That concept of custodianship went through my family; it has gone through my family for generations. So I just remember when I was a little child, he would look at Pohutukawa - the New Zealand Christmas tree - and he would use that as his yardstick, like I use the silver wattle. If it flowered early, he knew that he was going to have a long dry summer. He was a dairy farmer, so he was interested in production, but that's okay. If it was not yet in flower at Christmas time, then he knew that he was going to have a better season.

Those connections were passed down to me, so those are the things that come naturally to me. So for me, the seven seasons was something that I knew that I could actually connect with, and that could be my starting point. But for everybody else, it's different. I would just suggest to try to find that one area that you're comfortable with and, and start there and not be afraid to try.

Jessica Staines:

That [crosstalk 00:21:44] failure is a real problem for many educators, that they're worried about doing the wrong thing. I make mistakes all the time as well, and they're not even mistakes, but their learning experiences. It's something that I learned from, and I probably wouldn't do it the same way a second time round, but it's that trial-and-error, reflective practise. As you're saying, and it's what I say as well: I'm not an expert, you're not an expert, but we're open to the learning process, because we really value the importance of doing the work.

I think doing it collectively as a team is really important. It shouldn't fall on any one person's shoulders to do the work. It should be all of you together and using your strength as a way in, I think is great. Because within your team, there are educators that are probably great at art and others that love reading or cooking. For you, it's that nature connection. But we all have different strengths, so to find that thing that you have a natural synergy with and use that as a way to begin exploring ways to embed an Aboriginal perspective is a great starting point. Because once you develop confidence in one aspect of your programme, it's so much easier to transfer that throughout the entire curriculum, but you have to develop that confidence first. So I think your approach is fantastic and it makes total sense to me.

Linda Price:

Yeah. You know what, it's interesting because a few years down the track of me being the one who's bold as brass, and I was just going to use the resources that we've found and that have been provided for us, such as the Taungurung language app. Now you can hear that language used by children, used by educators, and also used by families, interestingly. I know that what we're doing is making a big impact on our wider community. And I know that because people are feeding back bits of information, where they never did before. For example, a parent saying, "Oh, she keeps saying, this is 'bawang' over there. How does she know this is 'bawang' over there?" The magpie. It was Rose, and she said, "Well, Linda taught me and we learn it at Kinder."

I know that just those little things can make a big difference in the lifetime [crosstalk 00:24:16].

Jessica Staines:

Yeah, the ripple effects because they're going home and telling their parents. Wwe hear this time and time again on this podcast that parents are learning about Aboriginal culture and history and language from their three- and four-year-old children. It just goes to show that education is advocacy, and when one person passed on something that they know to another, that's what slowly begins to see change of understanding in broader Australian society.

I really think that what you're doing is amazing and thanks so much, Linda, for jumping on the podcast with me this morning and sharing and for writing in our book. I really appreciate it.

Linda Price:

Thank you. Thank you for the offer.

Jessica Staines:

Does your preschool have a Facebook page or anything like that where educators can follow and see more what you're doing?

Linda Price:

Yes. So we have a Facebook page at Kinglake Ranges CC, I think it is. I'll have to actually just double check that. Also our website is, kinglakerangescc.org.edu.

Jessica Staines:

Yeah. Awesome. I think a lot of educators would really love to see and follow examples of the Bush Kinder. Because I know your article, it just hooked me writing to see what you were doing. I think a lot of people need to see those real case study examples of what this work looks like in practise. I know you mentioned lots of resources in your piece, as well, of even books that you mentioned, like Benny Bungarra's 'Big Bush Clean Up'.

Linda Price:

Yes.

Jessica Staines:

When the children were interested in like collecting the rubbish and so forth. I think seeing those case studies and resources that are just your tangible experiences for other educators to grab onto and work out ways to translate that into their programme is like absolutely invaluable. So again, thanks Linda so much and... Oh, yeah. I'm with you again soon.

Linda Price:

Okie dokes. Thanks, Jessica.

Jessica Staines:

I hope that you enjoyed this episode and had a great little sneak peak between the pages of our new book, 'Educator Yarns'. If you'd like to ask questions or connect with me, best to join our Facebook group, the Koori Curriculum Educator Community, which is free for all of our listeners and members.

Next time on Educator Yarns, we'll be welcoming back Cassie Davis, who some of you may remember from season one. Cassie is an early childhood educator at Penrose Kindergarten, which is part of Wyndham City council. Together, we'll be talking about the different ways that she's both embedding Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal perspectives in part of her day-to-day programming curriculum.