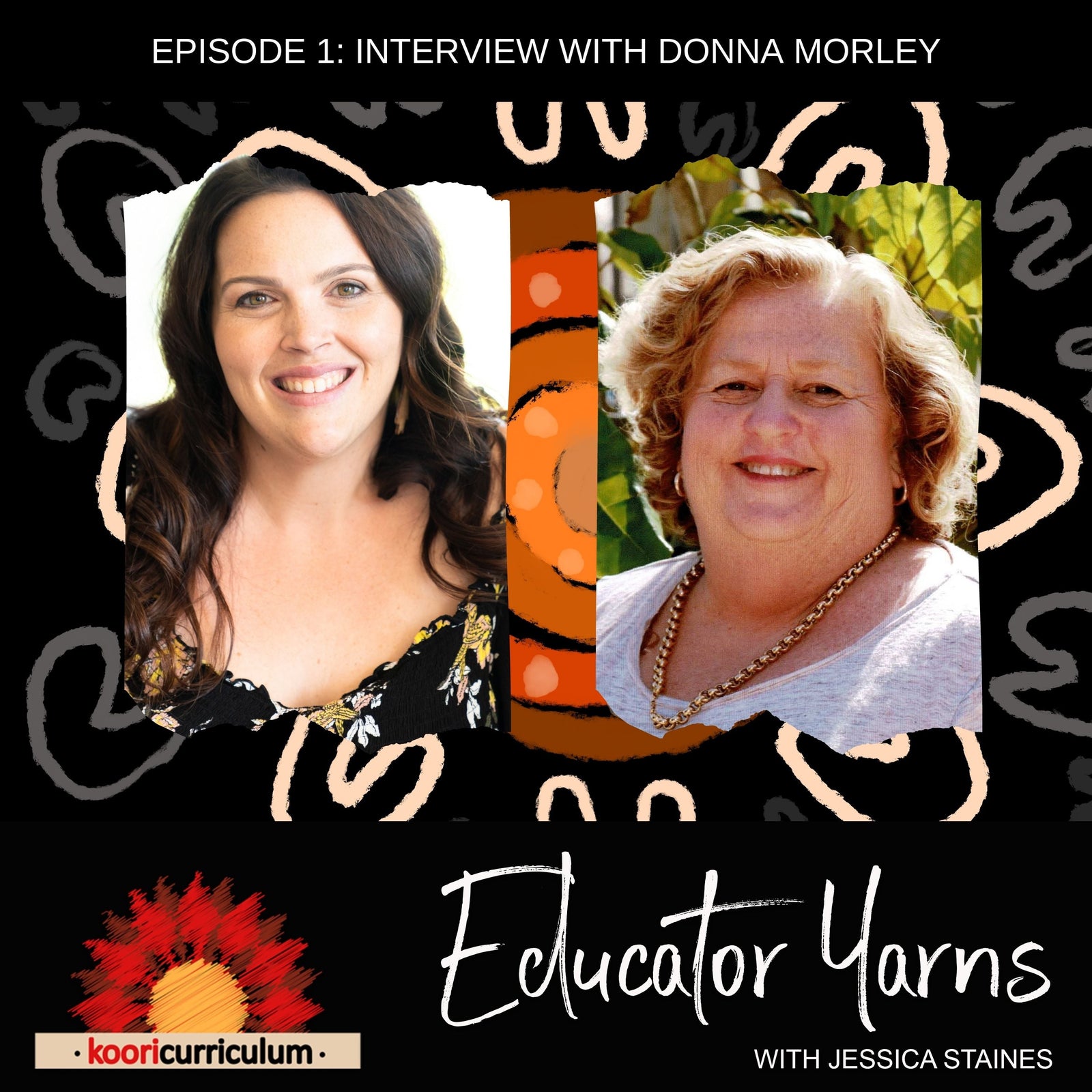

Educator Yarns Season 2 Episode 1: Interview with Donna Morley

Episode 1: Interview with Donna Morely

Today on educator Yarns Jessica speaks with Donna Morely and tackles the big question, how exactly do we tackle the big questions.

Donnas deep respect for children comes through in this interview as she discusses the importance of being honest, and open when answering the questions of children. No only to establish a relationship of respect but also to acknowledge the big world questions the children do have and do want answers to.

She reflects on the agency of the child and how begin conscious and open to the childs queries not only allows them emotional space to move freely in their thoughts but also encourages other staff to do similar and move along the same journey.

Donna is a wealth of knowledge and her understanding of the Aboriginal history and its place in the classroom is both refreshing and enlightening and a big win for the child.

Show Notes

Hi everyone. My name's Jessica Staines, Director of the Koori Curriculum. For those of you that aren't familiar with our podcast, season two is all about our new book, Educator Yarns. We're meeting and interviewing with the educator contributors from right around Australia, who will be sharing little snippets of their piece. It will be a combination of stories about why embedding Aboriginal perspectives is so important, how to connect with local community, how to embed Aboriginal perspectives in our programme, how to work with anti-biassed approaches and so much more. So, make sure you listen in and enjoy the episode. Bye for now.

Today on the podcast, we welcome Donna Morley, an early childhood educator who has been working in that profession for over 40 years together. Together we'll be yarning about whether or not we should be teaching young children about Australia's black history. Okay, thanks so much, Donna, for joining us on the Educator Yarns podcast.

Donna Morley:

My pleasure.

Jessica Staines:

And as we've been discussing, I thought that this episode would really be focusing on whether or not educators should or shouldn't be including Aboriginal history in their programme for children in the early years, because I think it's quite controversial in some ways. Would you agree?

Donna Morley:

Oh, absolutely. And I think we don't want to terrify children, especially talking about the stolen generations. Children can sometimes perceive that as a fearful thing that they might be stolen. They don't always understand it in the way that perhaps we might like to tell it, but I think there's lots of ways that we can explain all the parts of that history in a really sensitive way. So, I think you have to be really careful and know your children really well to know whether it's appropriate to have those conversations with them. But I did find when you have a group of children who start to learn about indigenous culture, and then they start to ask questions about Aboriginal people today, that they often will ask really quite challenging questions. And my policy has always been that if children ask questions, you answer the question that they ask, not necessarily what you may perceive.

So, if you're not sure what the question they're asking is, ask some more questions and delve down a little bit further so that you can work out what it is that they actually want to know. And then just answer that question, because if they're asking it, they're ready to understand it.

Jessica Staines:

Yup.

Donna Morley:

And that would go across all of my practise. That doesn't just go across Aboriginal content, it goes across everything. And I've always had, I guess, a deep-seated belief that it's much better to be honest with children than it is to tell them something that's not truthful. Because that then undermines the relationship because they then go, "Well, you didn't tell me the truth about that, so why should I believe you about this?"

Jessica Staines:

Yeah, it's really tricky, isn't it? So, there's one part of it that we sort of go, "Okay, if the children bring it up." So, we're not pushing this onto children, but if the children bring it up, then we're going to respond to them because this is their interest. This is their curiosity. This is things that they're thinking about, so we're going to respond. So, I think I agree with that part, but then there's also room, I guess, not everything that we do is based upon children's interests, it can be ideas and there's room for us and our intentional teaching as educators of concepts that we want to introduce. And so, I think there's that fine line to talk to children about history, but not put adult ideas on their shoulders. So, when I first began working in early childhood, I remember that we used to take buses of children because back then the risk assessments were a little bit different, but we used to take, essentially...

Donna Morley:

It was like, "Get on the bus and don't fall off."

Jessica Staines:

That's right. But make sure you've got all the kids when you leave. So, it was like... It was a little bit different, so we used to take all the kids down to the Australian Museum. And I don't know if you remember the old Aboriginal exhibition that was there with [crosstalk 00:05:23], and all that.

Donna Morley:

I do.

Jessica Staines:

Yes. So, we used to take them down and show them the bus. And there was a little chapel that was set up there, a bush chapel that you would take them into. And there was pictures of Aboriginal people in chains and all this stuff. And so, we would really talk to them about Australia's black history and the stolen generation. And then we used to take them across the road and sit at the foot of the statue in Hyde Park of Captain Cook.

And we would read The Rabbits by John Marsden, which is a very... Yeah. So, I mean, the thing is that I was 16 when I started working in early childhood. I'm not making excuses for myself, but the thing is, this is before the elf was even on the shelf, there wasn't a whole lot of ideas back then of how you go about including Aboriginal perspectives. And it was very thin-based. Teaching was my approach at the time, I guess. And I really wanted that education of history because I know so many educators just don't have it. But the problem is that it did traumatise a lot of children, and particularly, my practise began to change when I became a kinship carer, because I realised then more so on a personal level that the stolen generations, whilst the act, I think, officially ended in 1969 or something like that.

But it continues to happen today in the sense that we know that the numbers of Aboriginal children being removed from their families today is so much higher than it was back then. So, it continues to happen.

Donna Morley:

Yeah.

Jessica Staines:

And I think when we talk about subjects like the stolen generation, the first thing that children will say to you is, "Will this ever happen to me?" And as an educator that taught a lot of Aboriginal children how... And a lot of those Aboriginal children have spent time in foster care. I'm speaking, generally, different community contexts that I've worked in, how can I say to them, "Well, no, this will never happen to you." It's very tricky, isn't it?

Donna Morley:

It is. It's really tricky. And, I mean, I had a few indigenous children in my centre, but not many. So, we were mostly dealing with children from many, many different backgrounds, but not necessarily Aboriginal.

Jessica Staines:

Yes.

Donna Morley:

And they... But their parents were very keen for them to understand the history, but didn't necessarily want them to be frightened. So, we talked a lot about... I always talked about the history of Australia Day. And so, every year when Australia Day came around, we sat down and talked about what we did on Australia Day, what each family did on Australia Day, what other people might think about Australia Day, how Aboriginal people might actually feel quite sad on Australia Day, and that there's... And some of the children go, "Oh, that's what I want to change the date." So, kids are actually aware of some of those political movements that are going on in the periphery and they bring that to the table if you allow them to.

And I think that's really important. I mean, another time we actually were able to talk... I find art a really good way to get some of those conversations happening. So, we used to take the children to Barangaroo a lot, and sometimes they'd have big art exhibitions up there and they often have things with an indigenous perspective up there. So, we went up one time and they had a big sculpture exhibition, and they had on the hill, children called the rolling hills, so to speak large hill that faces out over the harbour, a sand sculpture that was written [Terra Ominous 00:09:03] across the hill in giant letters. And, of course, children are very interested in the letters and they're like, "What does that say?" And I told them what it said and they went, "Well, what does that mean?"

And so, we all sat down and talked about how Captain Cook came in and claimed Australia was terra nullius and what that meant. And, straight away, as soon [inaudible 00:09:23], he came and told them and Captain claimed the land is terra nullius. But the children went, "But the Aboriginal people were here. How could they say that?" And so, it comes from them to be able to have... When I say it comes to them, it doesn't necessarily come from them initially, but when you start to have the conversation based around a book or a piece of art, or some other stimulus that you might be using, a visit to the museum, for instance, then I think if you're mindful of the questions that they're asking and you respond to them honestly, then you can actually go down that path a lot.

The stolen generation, however, I think is a little bit difficult because I've mentioned it and we've certainly talked about it and it's come up in books that we've read and things like that. But I've probably will start a little bit and skimmed across it a little, not because I don't think it's important, but because I think that children at foreign font have very vivid imaginations and it may come a time when some of them... Like I did work in an area where there was some quite challenged families, and it could be that one of those children might need to go out of home care at some point. And I don't want them to feel like they're being stolen.

Jessica Staines:

Yeah, that's right. Because I think, well, no one's advocating for children to stay in scenarios where they're at risk of significant harm or any of those things.

Donna Morley:

Yeah.

Jessica Staines:

I think it's about the Aboriginal placement policy, generally speaking, not being followed the way that it should be and the privatisation of the foster care industry. But I think to the point that you were sort of saying, Donna, I think there's some key things that you've mentioned, and that is that your families were on board with this. So, they were supportive of it, and you were very mindful of the demographic of the families and the children that you were teaching. So, it's not something that you would just sort of doing on the hop, like it was intentional and thoughts through that had been done with consultation with families. And, I think, that's really important that your families are involved in the decision-making process when you're sharing sensitive content like this with children and that they... Because then they know that these conversations have been had, and they can follow up at home or debrief with children or offer some thoughts and suggestions. And I think that that's really key as well. And-

Donna Morley:

It's not, to say though, that we didn't occasionally have parents, who quite often though, parents I was really surprised at, that would bark at something. So, one family who had been really supportive of all the stuff that we'd done, I got a very lengthy email from one parent who asked for a meeting because her husband was British. And she was really concerned that she wanted her children to be proud of their heritage on both sides. And she was worried that if we were talking about Australia Day and the British fleet coming or talking about Captain Cook or any of that sort of stuff, in terms of an Aboriginal perspective, that we may be disparaging their British heritage. And I said to her, "The British heritage is also my heritage." I'm about 50 generation Australian, but it is definitely my heritage.

So, I said, "It's not about telling children that the British were bad. It was just.. In that historical moment, this is what happened. They invaded this land and the Aboriginal people were here, but they didn't recognise the Aboriginal people as being here. They called it terra nullius." And she was like, "But you're telling them that the British are bad." And I was like, "No, I've never, ever told them that the British are bad and they've never accepted that." I said, "Have you talked to them about it?" So, she went back and talked to them and they were actually able tell her that there were big boats with big sales and they were more interested in the boats really.

Jessica Staines:

Yeah.

Donna Morley:

But they also understood the concept that there were people living here that the British people didn't recognise. And we had a really long conversation with that group of children around why the British might... No, one of the questions was, "Well, why didn't they know that the Aboriginal people were here?" And we showed them some old prints of interpretations of when Captain Cook landed. And there said, "All these Aboriginal people were there, how did they not see them?"

Jessica Staines:

I think the thing is... And this is where it can get complicated because we know why. Because it was a very Darwinist type belief that they believe that Aboriginal people were not human beings. So, I think, it can... I understand that it can get complicated. And there's a quote that's been circulated on Facebook and around the place for a long time. And, essentially, it's something to the effect of no one is asking you to apologise for the actions of your ancestors, but it's about understanding how the systems and structures that they established continue to oppress and disadvantage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people today. So, and I guess that's why-

Donna Morley:

It was interesting, though. It was interesting and when we were looking at that art print of Captain Cook and his people in their clothes and their boots and their funny hats and all of that, which were quite ridiculous in today's lifestyle too. The children were... And I said, "Well, why do you think? Have a look at the picture, why do you think they might've not thought that these were people? Or why would they have thought that people didn't live here?" And they got it. It was so clear that they did. And then one of the children said, "Maybe they didn't think there were people because they didn't dress like them." Maybe there was some other reasons that they didn't think they were people.

And I just thought it was a really interesting conversation because it came from the children and we were able to have this really in-depth conversation, not blind down any answers at all, but getting them to think through, well, from an English or from Captain Cook's perspective, what would he have thought from the people who were on the land? The Aboriginal people, what would they have thought about these people coming that were dressed like that, that were very different from them?

And there was a really rich discussion with all of the children about how different people in different countries dress differently, how they do things differently, how they ate different food and how that we know now that all of those things are part of humanity, but maybe they didn't understand that back then. And so, but the kids came up with that, that didn't come from me at all.

Jessica Staines:

Yeah.

Donna Morley:

And I thought that was a really... And with other groups, the conversations gone completely differently, but with that particular group, and then... So, that child was a really deep thinker that went home and said to his parents all about the people who came from England, but didn't recognise the Aboriginal people and his mum had gone off on these huge other tangent without really listening to what he was saying. And it was about that really deep thinking that the children can do.

And when I talked to her about how surprised I was at some of the concepts that he'd come up with from different perspectives and how proud I was that he was able to think through something from two different perspectives, which I thought was quite extraordinary for a child who had just turned four. And so, I put it to her like that. And she was like, "Oh, I think you need to talk to him a bit more because it's not about his British heritage or the British being bad. It's about people in a different time seeing things in different ways, and how would each of those people putting on their shoes and finding out or getting inside their skin and finding out what they might've been thinking and feeling at that time." And that was a really, I guess it was a really good lesson in diversity and perspective and taking another's perspective.

Jessica Staines:

Yeah, and I think what he's been able to achieve at four years of age is something that a lot of non-indigenous educators are still trying to achieve now as adults. And that is that understanding how your world view can be very different to the indigenous children and families that you were teaching in the service. So, trying see things from another person's perspective is, as you're saying, quite an indicator of critical thinking that's going on. And I think when we're aware of our worldview and how our experiences, relationships, and opportunities have been different from other people from cultural and linguistically diverse backgrounds that we're teaching, it allows us to connect because we're mindful and intentionally teaching in that way. And, I think, celebrations is something that can have a greater capacity to exclude than what it does to include.

And Australia Day is definitely one of those, you know, celebrations that I know we struggle with. And I think the other thing that's really mindful to say is that the service that you're talking about, it was an inner city service?

Donna Morley:

Yeah.

Jessica Staines:

And I think a lot of the families just through my experiences with them was they're quite socially just and aware and mindful that they're wanting to teach these children these things. And I only say that because in previous years gone by, we used to volunteer and run children's day activities at the Yabun festival in the Jarjums tent, which is this five or day feast festival on the 26th of January. And yourself and educators from your service came and volunteered to deliver experience and activities on that day. And many of your families attended that festival through that connection. So, I think this is something that they were really trying to foster, and I know as well, even previously, to having done that you were doing... What was the name of the festival you were involved with?

Donna Morley:

Yeah, the [inaudible 00:19:35] for NAIDOC week.

Jessica Staines:

Exactly.

Donna Morley:

That's what it was called, yeah.

Jessica Staines:

Yeah, you would have a little tent store down there and I'm showing your service and your documentation and families would come and be involved in that. And, I think, this is where cultural safety in a way that's showing up in community events. Like you're not just teaching this stuff, you're actually involved and your taking part in developing relationships and bringing your families along on that journey with you was a big part of that, I feel?

Donna Morley:

Yeah. And, I think, we always started any celebration that we had with families. Any family day or anything like that was always started with, if we could manage it, if we could afford it in a budget, is making ceremony. But if not, we always did an acknowledgement to country. Either one of the stuff would do it, or one of the children would sometimes do it. And then I would always talk to the fact that this was included as a really important part of every function that we had. And that was because we wanted the children to understand the history of their country and that we had such a diverse group of families that we couldn't possibly honour everybody's culture authentically. And so, we chose as a staff to use the Aboriginal culture as the right of every child to know about because they live on this land.

So, it's such a rich culture to be able to share that with the children living here, whether they're living here for two years or five years, or if this is where their life is going to be for the rest of eternity. Then we felt that that was their right to understand this really rich culture, and to learn about it and find out about the history of the country and the land that they were living on. And the children were really mindful of that. They actually had learnt that from each other, I guess, as they were growing up. And you'd often hear them talking about how we have to really care for the land and all of, "That plant looks a bit sad. We better water it. We've got to care for the land." And they had some relationships with some Aboriginal elders who we were very fortunate would come past quite occasionally, and some more regularly than others, but they'd pop in and talk to the children about some of these things that were so precious to them.

And I remember uncle Clarence used to come and visit us. And he would say quite often things to the children like, "When I'm on my land, this is not my land, but when I'm on my land, it's like when you get out of bed on a really good day and you know that everything's going to be great today. The sun is shining and you just feel fabulous. That's how I feel when I'm on my land, it just regenerates me. And that's why I need to go home to my land every now and then, so that I can feel like everything's going to be great." And they used to talk about that. They'd say, "Oh, when we were on our land..." And they... It was just really interesting the way that they embraced that concept of looking after the land and being connected to it.

And I think that that sense of place for children in a world where they're often being moved around... So, quite a lot of our children were from families that were expats and were moving from country to country every couple of years. So, having that understanding that place is really important and they could link to that and feel a connection with the land, wherever that might be, was really important for them. And, I think, some of the practitioner research that we did was around that sense of belonging to a place. And it was really important, I think, for them to feel that connection, but that came initially that thinking around why it's so important to children and developing those ecological identities and all of that stuff which was very much based in the Aboriginal culture stuff that really we're doing with them.

Jessica Staines:

Yeah.

Donna Morley:

Does that make sense?

Jessica Staines:

It makes complete sense. And I think it's that idea of place-based pedagogy that is really key. And even though you're in the middle of the city, you're still on country.

Donna Morley:

Yeah, it does.

Jessica Staines:

That country isn't necessarily in the middle of the Bush somewhere. So, I think they're... And that's why before we started recording the podcast, you and I was saying, "Oh, we could talk about so many different things." Because there's just so much that I know that you can share and you have shared in the book, Educator Yarns, but I think it's hard to de compartmentalise those stories because one flows in to the other and a lot of them are happening simultaneously at the same time.

Donna Morley:

Absolutely.

Jessica Staines:

Because we could go down that rabbit hole of talking about reconciliation action plans. And I know the other thing that you're really keen to talk about was, and you did in your piece, is that... The line that I quoted you saying is, "Aboriginal perspectives are so much more than artefacts and artworks." And that really, yeah, it struck a chord with me because it is. And if you do have those artefacts, using them functionally and not just having them as a display piece to something, that's ascetically pleasing. And it's about really getting to the crux of it. And it's about identity and belonging and place. And if you are somebody that lives in Australia, regardless of your cultural heritage, Aboriginal culture is part of your identity as an alien. And, I think, everyone has the right to know about this country's history. And, I think, it's really important that they do know so that these mistakes don't repeat themselves and they need to understand what happened to understand what's happening now.

Particularly, when we look at Australia's current affairs and issues that continue to affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, dare I say the Black Lives Matter movement, so people really need to understand, and you and I both know as TAFE educators that many of our students that we teach, whether they were born here or they're international students, only know the tip of the iceberg regarding this country's black history. So, I really feel that, first as educators, there needs to be some cultural capacity training to some extent, to really develop the educators' confidence, to be able to include and make those links about Aboriginal culture in history. Because you yourself knew about terra nullius, but many other people don't. They don't know what that means, and they don't understand the difference between a country that was invaded and a country that was colonised, and how that lack of treaty continues to affect Aboriginal people today.

Donna Morley:

That's right. And I loved the children that were in that group. They were so perceptive. They saw that artwork that was set there for ages and I had a bit of a laugh because one of them said, "I've met that Captain Cook." And I said, [inaudible 00:26:53] And he said, "Yeah, I went on his cruise.

Jessica Staines:

On the tribal warrior. Oh, the Captain Cook, the cruise ships?

Donna Morley:

Yeah. He said, "If I'd have known this, I would have had a [inaudible 00:27:06]."

Jessica Staines:

Did any of your families ever do the tribal warrior cruise that was down there at Barangaroo?

Donna Morley:

I don't know. [crosstalk 00:27:16]. One or two of them may have been, but I tried to organise it at one point and it didn't quite work. We had... I can't remember what happened, but there was some disaster, weather or something that-

Jessica Staines:

That's all I remember you were trying to do something. Because I know that a lot of your families were always down there at the black markets and doing workshops and stuff. So, it really did have a cultural change.

Donna Morley:

And I did have a couple of staff that were from the Eastern Europe block, and they had got so into it that they were volunteering at the black markets doing all sorts of things. So, it went through everybody in the centre who would come in with all these really interesting things that they'd found if they were somewhere. They'd be like, "Oh, I saw they had original artwork and it was so fantastic. And I want to share it with the children." Or wherever they had been, they'd find something, and they were obviously on the lookout for those things. Because, I think, in the prior to that, they would never have noticed those things.

Jessica Staines:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Donna Morley:

So, I think that's helpful too as people become more aware of these things, then they start to find resources and find things that they want to talk to the children about. And I think because we were so open and honest with the children and took whatever opportunity came to have those conversations, then staff started to feel... As they understood more, they felt more comfortable with having those conversations as well.

Jessica Staines:

Yeah.

Donna Morley:

And some of those conversations sometimes got quite awkward and quite difficult and that's okay. But we always said that we would always be honest, but we'd be very careful to work out what the children were actually asking rather than telling them everything and having them feeling not sure or confused. When you tell children, it be sex education, you only answer the questions you really they're really asking. You don't have to give them everything. And they say where the babies come from, they don't want to know about all those other things.

It's the same thing with gay stuff. I think with some of the sensitive things, you have to be really mindful of the child that you're talking to. You have to be really mindful of... I guess, it goes back to those Australian teaching standards as well. Things like knowing your children really well, knowing your families, having those conversations openly with all of those people and making sure. And if we had had an awkward conversation during the day, something that a child might've responded to or ask some really difficult questions that we'd answered, we would always let the parents know the conversation that we've had.

Jessica Staines:

Yeah.

Donna Morley:

Because we wanted them to feel informed, but also, I suppose, comfortable with the fact that we were having those conversations. And if we had conversations with the children, we would let them know so that they were aware and didn't get swept out of left filled with something that they couldn't answer.

Jessica Staines:

Mm mm (affirmative). And, I think, that's it. It's not necessarily what you do, it's the way that you do it, which I think is... You're like, "Yes, you can include Aboriginal history, but it's how you do those things in a respectful way and in age appropriate way. That I think is the conclusion of our episode. And, I think, also revisiting your "why" to make sure that this is from the children and relevant to what they're doing. That it's not tacked on and separate, and it's not pushing adult political ideas and agendas. Whilst, I think, that children are capable of thinking critically and looking at policies and politics and all that stuff, I think it's relevant and meaningful when it comes from them. And it's not put upon them in that sense.

Donna Morley:

Absolutely.

Jessica Staines:

Yeah.

Donna Morley:

Yeah, absolutely.

Jessica Staines:

Well, thanks so much, Donna, for jumping on and yarning with us and for people that are listening that would like to know more about Donna's journey and her thoughts and ideas, be sure to grab a copy of Educator Yarns once it launches and read her piece. It's actually the first piece, Donna, in the book. You're opening?

Donna Morley:

That's special.

Jessica Staines:

Very special. Well, thanks again, Donna.

Donna Morley:

[inaudible 00:31:32].

Jessica Staines:

Yes, [crosstalk 00:31:33]. Thanks. I hope that you enjoyed this episode and had a great little sneak peek between the pages of our new book, Educator Yarns. If you'd like to ask questions or connect with me best to join our Facebook group, the Koori Curriculum Educator Community, which is free for all of our listeners and members. Join us next time, where I meet with Narelle Avis, Director of Cooma North Preschool. Together, we'll be yarning about the challenges that she has had in connecting with her local Aboriginal community in a regional area, and the strategies that she's adopted to overcome this.